For men may come and men may go,

But I go on forever.

– Alfred Tennyson, ‘The Brook’.

Introduction

The Significance of River History

When searching for a location to build a home, the humans who founded the first settlements on the Tyne had several priorities in mind. First and foremost, they needed access to a sustainable source of food and water, but they were also looking for a site that was defendable, sanitary, and well connected, to facilitate fast travel and trade with the outside world; the river was the only logical place that satisfied these objectives. Soon many human settlements had clustered around the Tyne’s banks and over time the people of Tyneside built their houses, economies, and cultures around the river upon which they relied for survival and expansion. As time progressed this bond grew tighter as they discovered that the waters could be utilised for other purposes; generating power, producing chemicals, concrete, oil, and many other industrial materials, as well as in being a source of recreation. In this way they followed the global human trend of using the river as a basis for civilisation. Likewise, the Tyne itself, alongside all the other life it supported, found its fate acutely entwined with human developments.

As historical agents, rivers and the life they support have never acted as passive resources to merely be consumed; time and again they have proved to human populations that they can knock civilisations down as easily as they built them up. In c.5000BCE, the fortunes of the peoples of Mesopotamia were dashed against the banks of the Tigris-Euphrates after repeated flooding, partially blamed on their own attempts to direct the path of the river. In c.2000BCE a 200 year drought hit the Indus river and spelled equal disaster for the peoples of the Indus Valley civilisation. In c.350BCE, it is theorised that the Guadalquivir river delta rose up to completely submerge the wealthy city of Tartessos based upon it, thus creating the origin of the Atlantean myth. In contemporary times rivers have become more entwined with human societies than ever, relied on as sources of food, water, culture, trade, and recreation, however they are also facing some of their greatest threats from the same source. The quantity of pollutants being discharged into waterways such as the Nile, the Ganges, and the Yangtze, as well as the effects of landscaping and unsustainable water use, is resulting in ecosystem collapse. This has resulted in ever-increasing quantities of resources being spent in efforts to save these unique environments both for their own sake and for humanity at large. The story of the relationship between human and river is an ancient one, and in the modern day is as important as it has ever been.

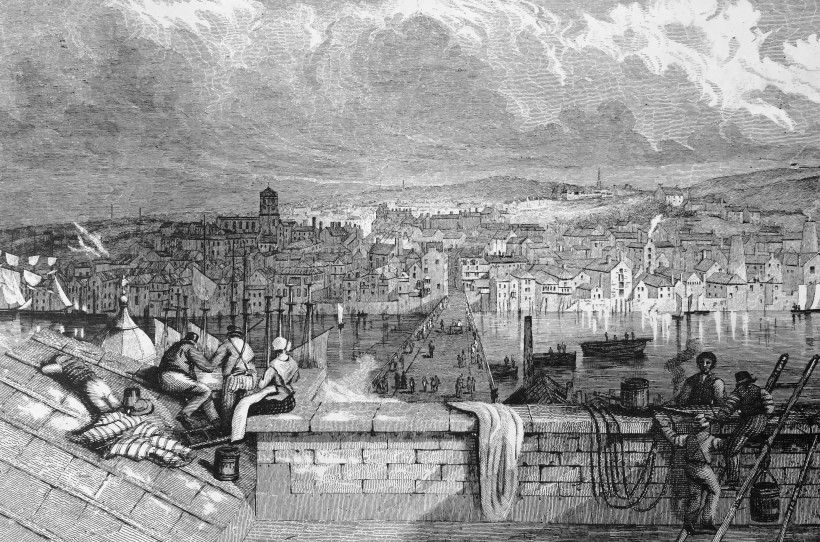

Across history the story of the River Tyne is one that parallels that of the modern Nile or Ganges, and it maybe holds some lessons for them. The pertinent period to assess in regards to this began in 1850 when a body named, in retrospect perhaps ironically, as the “Tyne Improvement Commission” was appointed by parliament to increase the volume and profitability of trade on the river. This organisation’s conservatorship of the river would last until 1968, and whilst not solely accountable, it was predominantly responsible for the transformation of the river during this time from a natural estuary into, in their own words, ‘a great highway of industry’. Environmentally speaking, their century of “improvements” meant that in 1957, when the Tyne’s waters literally bubbled with noxious chemicals, the river was officially classified as ‘biologically dead’.

Methodology and Historiography

The focus of this article is therefore upon the Tyne Improvement Commission (TIC) and the unprecedented changes that they oversaw during their 118 years of authority. The primary route of analysis is through the extensive records that the organisation kept of their proceedings, documenting step-by-step how they went about their program of transformation. From an environmental perspective, these sources are used to assess the impact of the TIC’s works upon the river and its ecology and how those impacts then affected humanity in turn. Their discussions are also analysed to come to an understanding of the philosophy behind their actions. Ultimately it is a study of the relationships, both physical and intellectual, between humanity and the rest of the natural world as they developed during the TIC’s tenure and the ways in which they intersected with one another. A river is a complex, interconnected ecosystem where disturbances on the waters can ripple outward beyond foresight, therefore it only makes sense to assess it as such.

What this article also provides is a counternarrative to the traditional histories of the region. Much of Tyneside’s modern identity has been built on its industrial heritage, for which it is proud, and a significant majority of its written history has forwarded a narrative where the river’s “golden years” are the same as those which resulted in the pollution and destruction of much of its natural resources. The modern Port of Tyne describes the appointment of the TIC as the beginning of ‘the heyday of the river’, but from the perspective of the river itself this is far from the case. It would be untrue to say that environmental concerns have been omitted in entirety across the historiography, although this is sometimes the case, but it would be fair to state they have been largely disregarded. The history of the Tyne’s shipyards, mines, and factories is far from something to be ashamed of, but it is, this article argues, something to be reconsidered and taken in duality in the light of an understanding that the benefits of industry came at a significant cost.

The predominant concentration of previous histories of the river has been on the human activities that took place upon it; the history of export statistics, employment rates, and commerce. In 1880 James Guthrie’s The River Tyne: It’s History and Resources gave little attention to ecological concerns, focussing on the feats of engineering that had been so successful in remodelling the river’s form in his recent years. Throughout the 20th century this trend continued with texts that also focussed predominantly on human achievement and engineering such as Life on the Tyne, The Origins of Newcastle upon Tyne, and Maritime Heritage: Newcastle and the River Tyne. The same is true for the texts of the 21st century, such as The Story of the Tyne and River Tyne. All of these are fine publications which competently examine many aspects of Tyneside’s history, and indeed all were useful in the writing of this article, but it must also be said that they neglect environmental angles. Not all histories can or should be environmental histories, but the extent to which the natural history of the river has been buried beneath fascination at industrial achievement, even to this day, is surprising.

One text, however, has acted as an exception to this rule, and has taken an ecological approach to the river’s history, this being Leona Skelton’s Tyne after Tyne: An Environmental History of a River’s Battle for Protection 1529-2015. Tyne after Tyne looks at the history of human environmental action and conservation on the river and therein Skelton analyses how approaches and attitudes to the Tyne have varied over time regarding conservation of its natural resources. This study has opened the field of environmental history on the Tyne and has revealed a forgotten and often ignored, yet fundamentally integral, facet of its past. Where Tyne after Tyne covers a broad time period however, this article more tightly directs its attention toward one specific stage of the Tyne’s environmental history, exploring it in greater detail and looking at the physical effects of that environmental action upon the biosphere.

The importance of the relationship between human and river is one that has always been appreciated on the Tyne, but the importance of an environmentally sustainable relationship is one that is now having to be re-remembered. Indeed, for a majority of its history before the formation of the TIC, the citizens of Tyneside managed to live in comparative harmony with their river, and not because they lacked the technology to do it harm, as the Mesopotamians prove. It is crucial therefore that we understand the pre-industrial history of the river as both comparison and context within which to assess the momentous changes it would face post-1850 which so fundamentally shifted the ecological landscape.

Chapter 1

More lasting value than californian gold

The Deep history of the tyne

The history of the River Tyne began at the same time the British Isles rose from the sea 30 million years ago. Just north of Kielder at the Scottish border the north Tyne emerged and meandered eastwards before travelling south towards Hexham. The south Tyne began in Cumbria, flowing over the limestone rocks of Cross Fell and feeding into the north river at Warden Rock. At this meeting point they then processed eastwards, sculpting a valley out of the chalk which had formed 40 to 80 million years before. The formations made during these early chapters in the Tyne’s history have proved influential on its development thereafter, the movement of glaciers and other fluvial processes being the key instruments which created the landscapes and habitats that have dictated the character of the valley ever since. The result of these processes was that the Tyne region became naturally isolated from other parts of the country, establishing an environment that was ecologically unique for the plants and animals that occupied its banks. After humans arrived, this isolation drew people closer to the river as it created a greater need for water-borne trade.

These ancient geological processes created the environments on which all life in the region has since been based, the Tyne’s mudflats, riverbanks, and tributaries encouraging the specific types of flora to grow and fauna to breed that have since become local to the region. Pink salmon, river otters, and water voles alongside rarer creatures like the kittiwake, white-clawed crayfish, and the freshwater pearl mussel all chose the Tyne for these characteristics, as did the human. Outside of wildlife, the prevalence of lead and coal on the banks of the Tyne has been extremely influential on its history ever since mining started in the 2nd century, and the abundance of gravel on its riverbed became a valuable resource in the creation of concrete in the 20th.

Preservation for Profit: The Corporation of Newcastle

The corporation of Newcastle could be described as the progenitor of the TIC, although the two organisations took considerably varying approaches to managing the river. It rose to prominence in 1319 when it was granted royal conservatorship of the Tyne between Sparrow-Hawk and Hedwin streams at the expense of rivals south of the river (in this context “conservatorship” meaning the preservation of commerce, not ecology). Soon after it acquired exclusive royal licenses to dig coal in 1330 and by 1530 it had been made illegal to load or unload goods anywhere along the river except from the city of Newcastle. Through taxes, trade, and tolls the corporation absorbed the majority of the Tyne’s profits and became efficient in preventing other townships from tapping its wealth. Alongside hundreds of minor blockages it brought major successful petitions against South Shields, Jarrow, and the Bishop of Durham to prevent them loading ships, building wharfs, and exacting tolls. In this way, the Newcastle Corporation acted as an unlikely force for ecological preservation, preventing redevelopment of the river as a means of blocking rivals’ opportunity to turn a profit.

The nature of the corporation’s trade, being predominantly in hides alongside wool, fish, and corn (although coal was profitable and growing) also acted as a force for environmental conservation. These industries, being based on natural products, were considerably more reliant on the health of the river than those, such as coal, which would dominate the Tyne in later centuries and so this gave financial incentive for the Newcastle corporation to care for it. Local flora and fauna was also what the population of Tyneside predominantly survived upon in terms of sustenance as well as economics. Additionally, even if it did not fully understand the science behind the impacts of dumping in the river, the corporation was still very aware that its relationship with the Tyne was a ‘two-way process’, that their fortunes were bound; knowing the river’s tides and currents, and knowing where it was shallow or deep, or the best spots for fishing, was integral knowledge for the corporation’s success. It knew that the status-quo was profitable, and was therefore wary of change.

The way the corporation managed this was through a “river court”, which it set up in 1613, soon followed by a conservancy commission in 1614. The river court, complete with river jurors and water bailiff, was held weekly and was used to impose fines on those who would ‘do harm’ to the water. This was meant in an economic sense, but it is clear that environmental and economic prosperity were inseparable in these cases, as they were so closely tied together. This approach was very effective, and Newcastle-upon-Tyne grew wealthy as a result of it. William Brereton, after a visit to Newcastle in 1635 remarked that it had become ‘the fairest and richest town in England’.

Ballast Dumping in the 18th Century

However, the impression must not be given that the river laid completely unsullied before the advent of the TIC. The Newcastle Corporation was not an environmentalist organisation and its river court was not created out of a desire to protect the natural world for its own sake. This is best shown by looking at the 18th century, in which the extent of trade on the river began to increase substantially. For many years beforehand ships had been dumping ballast into the river with less than stringent regulation; the entirety of Newcastle-Gateshead’s quayside had been created via a slow process of the filling in of old docks with silt to eventually form a platform of land. By the 1700s however, the extent of these depositions was causing the already narrow and shallow waters to grow narrower and shallower; indeed, at low tide you could wade across the river at the point where the present swing bridge stands. More importantly for traders however, the tides were pulling the ballast downstream towards the mouth of the river where it was feared the ports would become clogged to such an extent that commerce might be halted altogether.

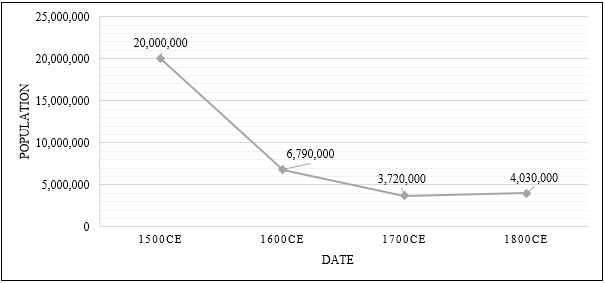

The health of the ecosystems within in the river were also being affected, as the sediments were burying habitats, thus reducing aquatic diversity. However, ultimately the environmental impact was not highly significant because it did not fundamentally change the environs of the river as the dredging of the same material would do in later centuries. The Tyne was already a shallows environment and the ballast, whilst causing some damage, did not alter this and was composed of non-toxic natural materials such as sand, mud, and rock. The ecological records available from the time, concerning concentrations of fish in the river (important to the fisheries of Tyneside) endorse this point, suggesting that the river was not only as healthy as it had ever been but was, in fact, healthier. It was recorded that on a single day on the 12th of June in 1755 more than 2,400 salmon alone were caught from the river. In comparison, over the entire month of June in 1996, only 338 salmon were recorded in the Tyne. The 1755 numbers may have been even higher without the dumping of ballast, but levels of local life were evidently not notably adversely affected.

In principal the corporation had always been against unlicensed ballast dumping into the river, this was partly the reason behind setting up the river court. In this case, however, it did not strongly push back against this process. Predominantly this was because these build-ups of sediment were creating new land along the riverbank, valuable land which, under the law, automatically belonged to the corporation. In this case, even after it was allotted government money to clear the silt in 1765, the corporation took the opportunity to turn a profit at the environment’s expense. Given the catastrophic impact that dredging would have on the river under the TIC however, it could equally be argued the corporation unwittingly took the more environmentally conscious approach in this decision. Either way, complaints from navigators on the state of the Tyne continued well into the 19th century.

The Enlightenment and Proto-Industrialisation

Whilst humans’ physical relationship with the Tyne may not have changed substantially in the 18th century, what did change was their attitudinal relationship; a shift which laid the groundwork behind the ideology of TIC. The enlightenment was the primary movement behind this change in relations, a philosophy with humanism at its core and a belief that scientific empiricism would lead humanity towards the conquering of the natural world. For the rational, orderly ideals of the enlightenment, the mercurial, muddy, meandering Tyne was something antithetical, something to be controlled. However, after these philosophies became popular the Newcastle corporation did not immediately set off on a crusade against the Tyne as the TIC later would, for three main reasons. The first reason was, as previously explained, that the corporation had been made extremely profitable by specifically avoiding tampering with the river’s natural systems. The second was that it lacked the technological ability to landscape a waterway such as the Tyne, or at least the ability to do it in a way that would not be prohibitively expensive. Thirdly was the fact the organisation’s frameworks and regulations had been set up hundreds of years before the advent of the enlightenment and adapting to fit this new ideology would mean a reinvention of what the corporation had stood for since 1400, a reinvention which never took place. It was also the case that enlightenment ideals were not fully pervasive, and many people, especially those in nature-based industries such as fishing, were sceptical of attempts to control it. Even in 1850, on the formation of the TIC and at the height of frustration with the Tyne’s unnavigability, the Shields Gazette wrote an endorsement of the river’s natural state, saying it was ‘of more lasting value than… Californian gold’.

By the beginning of the 19th century however the physical landscape of Tyneside was beginning to match its ideological, despite the inactivity of the corporation. At Derwentcote, Winlaton, and Lemington were ironworks, and two glass manufactories. At Blaydon was a lead refinery, a flint mill, and a large pottery and at Derwenthaugh was a coke manufactory and coal tar ovens. The first Tyne tunnel was built at Wylam to transport coal under the river. The river was also home to two coal staithes and a number of lead mines, both materials having been mined on Tyneside since the Romans built its first bridge in 122AD. These were the first buildings to begin washing substantively harmful substances into the waters such as coke breeze, benzene, naphtha, ammonia, and phenol. However, without chemical testing, at this stage these industries were too new and too few for people to properly appreciate the harm they were causing to the river. An 1827 report from the topographer Eneas Mackenzie does approach this topic however, noting that levels of salmon in the river may be declining because of the ‘deleterious mixtures that are carried into the stream from the lead-mines and various manufactories on the banks of the river’. It is evident from this statement that Mackenzie was somewhat aware of the environmental damage being done to the river but what is also evident is that he does not consider the decline in river life to be an inherently bad event. The fact is only mentioned off-hand and quickly forgotten in his excitement around the wonders of industry.

In 1816 the corporation commissioned the engineer Sir John Rennie to create a report of suggested changes to the riverfront. Therein he recommended the construction of two piers at Tynemouth, embankments along the river as far up as Newcastle, and multiple quays; all of which would have to be accommodated through a program of extensive dredging and landscaping. His stated goal was to ‘direct the river in a straight, or at least a uniform course’, an idea very much in line with enlightenment ideals. The corporation however, still unwilling to instigate change, did not act to implement Rennie’s suggestions and this increased the growing frustration at the state of navigation on the river. Thus, the Tyne Navigation Act was passed in 1850, which resulted in the formation of the TIC. The organisation immediately set about its work of dramatically altering the landscape of Tyneside and by the end of the century, it had implemented all of Rennie’s suggestions and more so, creating a deep and orderly channel. This quickly resulted in the decline of Tyneside’s keelmen, whose entire trade had been built on the premise that large ships could not navigate the river’s shallows, but it also resulted in severe declines in plant and animal life, as well as the overall health of the river.

Chapter 2

A great highway of industry

Reconceptualising the river

The works of the Tyne Improvement Commission completely transformed the face of the river on a scale that had only ever been previously achieved through millions of years of geological landscaping; they also began an era that would result in the worst pollution the river has ever seen. The men, and unsurprisingly for this time they were all men, who constituted the commissioners for the TIC were a mix of local councillors and business owners who’s trade was located in the riparian zone, the majority of which were based in the coal and shipbuilding trades. Whilst this commission was officially unbiased, the more wealthy and powerful members were often able to exert their influence for their own ends. In their proceedings for 1875 for example, we can see how Lord William Armstrong was able to rush through expansion plans for his factory at Elswick without the usual scrutiny period of one month.

Together however, the commissioners were united in a common goal, to make the Tyne as profitable as possible. This was the very purpose that the TIC had been set up for and its members ‘deeply’ believed in that task, with no thought towards environmental affairs unless they were to infringe on profits. Indeed, across all their proceedings papers of over 100 years of history the TIC demonstrates no discernible changes in attitude towards the river or their own purpose upon it; their proceedings in 1894, 1902, and 1945 all specifically stating that their prerogative as “conservators” of the river was not to look after its natural state, only to keep it in a condition suitable for facilitating trade. One proceeding from 1958, as the commission was reaching the end of its lifetime and as environmental concerns towards the river were growing in popularity, best demonstrates this intransigence. When the commissioner who represented South Shields, Mr. Gompertz, inquired as to the ‘risks we are running in further pollution of the river’, in relation to allowing sewage to be discharged directly into the water, the chairman, after some debate, responded that they had ‘no powers on that matter at all’. This statement is astounding given that the TIC specifically was the body that was responsible for the approval and regulation of sewage systems at this time. Evidently, they did not feel that environmental concerns constituted a legitimate reason for regulation in 1958, just as they hadn’t in 1850. They had similar reactions when requested in 1881 to help with the building of recreational facilities such as a rowing and sailing club, denying that this was their responsibility.

This consistency of approach and unified direction of purpose is one of the astounding facets of the TIC, and perhaps one of the reasons behind its success in so categorically remodelling the river. This was not an organisation that passively and indifferently carried out its task, it actively pursued a vision and cared deeply about its planned “improvements”. The Tyne needed to be competitive in a global context, with the infrastructure capable of matching other industrialising rivers such as the Thames, Clyde, and Rhine, which could also be called inspirators for the TIC. In 1876, long before most of their works were close to completion, they had already proclaimed that the Tyne was ‘the finest port in England… and the world’, listing its safety, capacity, and possibility as reasons for this. This attitude is completely maintained 75 years later in a document the organisation published in 1951 entitled A Century of Progress. In a manner that could almost be viewed as fanatical they write that ‘commerce is our life blood’; this was a capitalistic institution in its purest sense. In this manner the TIC bares some resemblances to the former corporation of Newcastle, both being organisations that were granted conservatorship of the river and both primarily being concerned with its economics. However, where the Newcastle corporation stood to profit from preservation of the river’s natural state, the TIC’s business model meant that it was indifferent to such concerns and payed them little attention. Indeed, as it stated in 1908, it would use ‘all that science and nature can offer’ to achieve its ends.

Dredging the river

In order for any of the infrastructural projects the TIC would undertake during its tenure to be worthwhile, such as the construction of docks, piers, and bridges, it first had to ensure that ships would be able to pass up the river far enough to access them. The solution to this was to dredge the river by removing the sand, rock, and mud that lay on the riverbed and dump them out to sea, a monumental task that had only been made recently comprehensible by the invention of the steam powered bucket dredger, the first ever of which had been employed in the neighbouring harbour in Sunderland. In 1850 the commission had access only to one steam dredger, which it had brought down from the river Tweed, but in 1853 they bought a second and by 1920 they had six all working to deepen and widen the river. These dredgers were tasked with ‘working day and night’ and so the citizens of Tyneside were forced to become used to their metallic clanks and churning coal-fired turbines.

The commission’s reports comprehensively documented these dredger’s activities, as the organisation was very interested in maximising their efficiency, but they did not monitor the environmental repercussions that came with such work. The tests they did carry out, the first of which was in 1895, were concerned with the dumping of solid waste into, rather than the dredging of it from, the river. This was not because of environmental concerns however, but because the commission saw that this would result in an inefficient dredging process, the material being removed only to be replaced again overnight. The same reports make no attempt to measure or regulate the chemical composition of the water, only the solid material. Even in the TIC’s earlier years it cannot be argued that this was because of a lack of scientific understanding as the Tyne Salmon Conservancy (TSC, the body which represented the Tyne’s fisheries) carried out its own rudimentary chemical tests as early as 1866, being understandably concerned about the unhealthy state of the river.

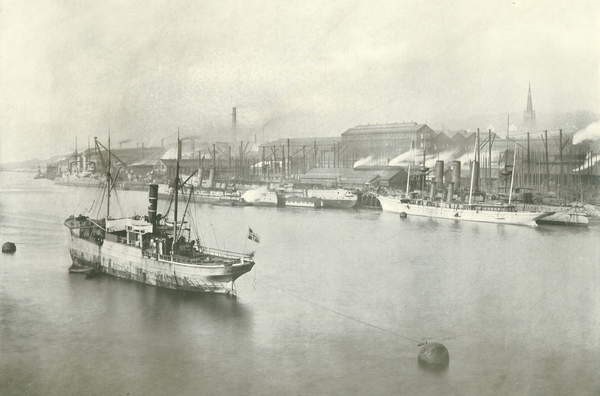

As the TIC was not concerned with such issues however, the dredgers continued their work and over a period of 70 years they deepened the Tyne from where it had lain previously at 1.83 meters to 9.14 meters. The commission’s own estimation for the extent of matter removed from the riverbed during this time amounts to the staggering figure of 149 million tons. This, alongside the TIC’s other infrastructural projects, had a huge impact on the capacity of Tyneside to trade on the river, with the Tyne becoming the largest repair port in the world by 1880, and the largest for the exportation of coal, producing 8,131,419 tons that year. Trade in total doubled on the river and the Tyne carried 1/9th of the total tonnage of the United Kingdom, second only to the Mersey, and built more ships than any other river aside from the Clyde. The cost of this was substantial to the TIC, over £3.5 million pounds (equivalent to £206 million pounds in today’s currency) which it managed to source from government grants, fundraising from local businesses, and its own taxation schemes. However, the cost was substantially higher for the flora and fauna of the river that soon found their habitats ripped from beneath them, a destruction which it is estimated will take hundreds of years to recover from.

The first and most evident effect of this dredging was the replacing of the river’s natural shallow environments with much deeper, faster-running waters. The problem with this was that much of the local plant life, including reeds, lilies, pondweed, and willows, were not suited to surviving in such a habitat and so soon began to disappear from the riverbank, as well as smaller fare like phytoplankton, algae, and zooplankton. The resulting collapse of the ecosystem overall was then the result of a domino effect as each creature in the food chain found its food sources diminished. Much of the plant life had also acted as a habitat and spawning ground for many shallow-water life forms such as crabs, worms, shrimps, and fry as well as for insects like dragonflies, water boatmen, and other small invertebrates like the caddis and the mayfly. This in turn meant a decline in the predators that eat such creatures such as the mackerel, flounder, and seal alongside birds like the heron, turn, and kingfisher. In areas of significant dredging, the result was the complete removal of a shallow-water habitat and the creation of a deep-water habitat, which significantly destabilised the local biosphere.

If dredging only resulted in this alone there would have been a possibility of ecological recovery in a relatively short time frame as whilst much of the local flora was forced out, some of the hardier specimens could have survived in the new environment; plants such as the sedge, plantain, starwart, and sharp rush. Other plants better suited to the new environment would have also moved in, such as cordgrass and seagrass. However, the impact of the steam dredgers went further than habitat destruction. All dredging by necessity causes disturbance to the riverbed but this early form of bucket dredging was particularly dangerous in this regard. The scoops dug far enough down into the riverbed to reach the benthic zone, the sediment sub-surface at the lowest level of a body of water, and if they didn’t, the explosives which were also used as part of the dredging process certainly did. The reason this was dangerous was that the benthic zone of the Tyne contained many chemicals of a toxic nature such as lead, biphenyl, and tributyltin, which were not protected from being released into the water as with modern dredgers, and as such they acted as biocides which weakened or killed plant and animal life in the river. This is especially the case when considering this period of disturbance lasted as long as 70 years, the prolonged deviations from natural water turbidity also affecting the metabolism and spawning of certain creatures such as trout and the seeding of vegetation like sea grass.

Whilst unenlightened as to the chemical specifics, the TIC could still observe the very clear fall in biodiversity on the Tyne and was to some extent aware that this was a result of its own work. Indeed, when writing a promotional piece for their port in 1925 the TIC not only acknowledges this, but is very much proud of this achievement, and not wholly unjustly due to the monumental feats of engineering that it required. Therein they write that whilst the old river may have been ‘picturesque’ it was now ‘the Tyne of yesteryear’, thus positioning the TIC’s modern creation specifically as the antithesis to ‘picturesque’. Overall the commission’s language in this document is indicative of their view on their own accomplishments, that they had made the post-1850 Tyne into something that was, conceptually, a completely different body of water to the pre-1850 article. In their proceedings of 1875, they wrote that their goal was to make the Tyne ‘equal to a dock’, to remove its status as a river entirely, by 1925 they believed they had achieved this. It would not be entirely incorrect to agree with the TIC on this point, as the ultimate result of their dredging program was the effective conversion of the Tyne from a river into a very large canal from Dunston downwards, as it remains today. What previously had been merely a river was now, in their own words, a ‘great highway of industry’. ‘Highway’ is the notable word to examine here, as it distinctly encapsulates the perspective toward the river which resulted in its conversion; that being a view of the river as simply a road made of water, a transportation device. The commission valued the river just as much as the Newcastle corporation or the TSC, perhaps even more so, but the nature of their occupations meant they no longer valued it as an environmental resource, only as a logistical one.

However, the relationship between the TIC and the Tyne was not so unidimensional, and the commission soon discovered that their program of dredging would, to some extent, need to bend to fit the Tyne’s will. Erosion was their primary difficulty, as the TIC soon found swathes of riparian land collapsing into the river, much of it their own, although they were reluctant to admit in their proceedings that this was a problem of their own causing. The problem persisted throughout the TIC’s administration, and they had to deal with the erosion problems caused by dredging into the 1950s and 1960s, long after they had stopped deepening the riverbed, in places as far up the river as Haydon Bridge on the South Tyne. The reason this was occurring was because the dredging process had increased the gradient of the river, heightening its power on its new steeper course, and thus causing more aggressive deterioration of the banks. This effect was intensified because of the straightening of the river, which meant much greater force was exerted against the riverside, and this consequently created the need for weirs and embankments to be built along much of the quayside, although much of the time the commission was forced to concede and allow the river to carve at the land as far in as it required.

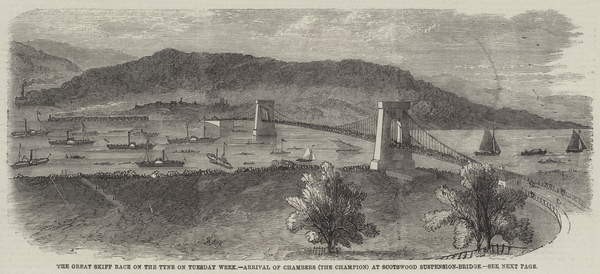

Further to this the dredging resulted in the forces that the tides exerted on the river becoming far stronger, making the waters more turbulent and unsafe to travel on, as well as causing further erosion and silting up the docks, ironically creating much more work for the dredgers. In 1881 tenants in North Shields complained to the TIC that the force of the river ‘shakes the building’ and the northern rowing club also complained the following year that their casting-off point had been made ‘excessively deep and dangerous’ because of this. Such problems also affected large structures such as the Scotswood bridge, the company for which wrote to the TIC in 1884 complaining that its foundations were being undermined and it was at risk of collapse. The use of unpredictable explosives for the purposes of dredging was even more dangerous, as proved when, in 1894, the dredgers came within ‘90-100 feet’ of breaking through the roof of a mine that ran under the river owned by the Montagu colliery.

The sheer scale of the dredging operation was also causing difficulties as the TIC found it increasingly difficult to regulate the process. Whilst there were only a handful of steam dredgers, there was a considerably larger number of ships known as “hoppers”, barges which were responsible for taking the silt from the dredging ships and dumping it into the North Sea. Two problems arose from this process. The first was that a number of hoppers were dumping their cargo too close to the shore and as a result it being washed back in to the river again, a problem which was expanded by the building of the piers at North and South Shields because they increased the area the TIC was obligated to manage. To combat this the TIC set a bylaw in 1885 that the silt had to be deposited outside of a three mile radius, but they still found that they were not always obeyed. Indeed, it was in the hopper operator’s financial interests to create more work for themselves.

The second problem arose slightly later in 1900, after the program had been running for a while; what they discovered was that the sheer amount of material being dumped into the sea was beginning to threaten the passage of ships into the port because it was ‘raising the bed of the sea’. This also created problems for anglers both on the sea and the river, who found their nets and pots periodically smothered with ‘masses of refuse’, and often submitted complaints to the commission. With all of its technological might the TIC clearly thought of itself as an organisation that was above nature, that could do with the Tyne as it pleased, but the river proved time and again to be a force that could not be easily constrained and occasionally it would remind the commission that they were sometimes bound to playing on its terms.

Reconstructing the River

The dredging of the Tyne was only the preliminary stage, however, in the TIC’s plan. The removal of 149 million tons of material from the riverbed being simply the groundwork required which would allow larger ships to utilise the commission’s key infrastructure projects, these namely being the piers at north and south shields, the Albert-Edward, Northumberland, and Tyne docks, and the Tyne commission quay. A lot of resources were also spent on supporting projects to these large constructions such as the building of embankments, the swing bridge, and the destruction of rocky outcroppings.

The construction of the Northumberland Dock in 1857 and the Tyne Dock in 1859 were the first major schemes to be completed under the TIC’s oversight, and work soon followed on another that would be named “Albert-Edward” in 1884. Significant excavations and further dredging was required for these projects, including the removal of tens of thousands of cubic meters of mud, gravel, clay, and sand; fortunately for the commission they received a good amount of private assistance in the removal as much of this material from firms such as the Wallsend cement company in 1877. This was especially true in regard to the gravel and clay, some of which was then used to create the base on which the docks stood. The Tyne commission quay, opened later in 1928, was built in the same manner and also with a small hydroelectric power station, an example of how the quickened current as a result of the dredging was utilised by the TIC to their advantage. This dredging caused all the same environmental problems as it did in the rest of the river but with the additional issue that the space was then entirely filled in with solid concrete, the Albert-Edward dock alone taking over 32,000 concrete blocks to construct, meaning the riverside and seaside ecosystems had no possibility of recovery.

The single project which caused the TIC the most strife was the construction of the piers at North and South Shields. Partly due to the fact that dredging had caused dangerous tides to progress up the river, work was forced to begin ahead of plan in 1854 in order to protect ships in harbour, but the piers would not be completed until 1895 at a much higher cost than the commission intended of £1,000,094 pounds due to repeated damage from the force of the currents around the mouth of the river. After completion the saga was not over however as the north pier lasted only two years before being destroyed in a storm in 1897, and was only rebuilt by 1910 after bringing the total cost of the project up to £1,544,000. During all of this difficulty, in 1878, the TIC decided not to remove the “black middens” which were situated in front of the north pier because of their function as natural breakers which protected the coastline and, importantly, the walls of the pier, stating they were to a ‘general advantage’. These middens were infamous dangers to vessels, wrecking five ships in three days in a storm in 1864, but they were nevertheless so useful to the TIC that they were preserved. This case demonstrates that the TIC did not see itself as being on a mission against the natural world in all contexts. If a feature did not hinder, or even helped with their work, as with the black middens, they would be happy to leave it alone. By the same token however, they would not pause a second for anything which obstructed them, no matter its beauty or significance.

Generally, the TIC was quite happy to remove natural rock formations along the river however, if they were to get in the way of their “improvements”. As example to the fact that not everybody agreed with the prerogative of the TIC, two petitions were set up by the general public, the first in 1881 and the second in 1882, which were filed against the commission in attempts to save two popular natural beauty spots, Frenchman’s Bay and Lady’s Bay. Neither of these were successful, despite the fact they were signed by a great number of people of noteworthiness, including the mayor of Newcastle, the naturalist John Hancock, and a number of scientists with interest in the areas. Therefore the TIC carried on, removing a number of ‘protrusions’ at Felling Point, Whitehill Point, and Bill Point (amongst others) during the 1880s and significantly widening the river in one area near the mouth to create the Tyne main turning circle; both of these projects required the determined use of explosives over decades to complete. This is an example of the power of the TIC itself but also of the belief in the importance of its work, both from the organisation itself and from outside. The industrialisation of the river was an imperative, this was “progress”, unarguable and inevitable.

Chapter 3

NEITHER SALMON NOR CHILDREN

Industrialising the River

The TIC’s tentpole projects such as the docks, piers, and dredging program, whilst being the most impactful single enterprises on the environment on the river, were ultimately a drop in the water compared to the wider industrialisation that was taking place along the Tyne. The TIC was responsible for approving and regulating all new industries set up in the riparian zone, this task including the regulation of waste discharged into the river, but for the most part they took a laissez-faire approach to this duty. Their purpose as an organisation was to help, not to hinder, the growth of industry, and as environmental regulation would have hindered, they left it alone. Instead they acted as facilitators for the mass production of coal, coke, oil, timber, pottery, concrete, meat, iron, steel, glass, a vast array of chemicals, and all of their waste products. All these industries were built around the river (along with a multitude of smaller businesses) and they used it to help produce their goods, to transport them when complete, and to discharge their wastes into. Alongside these were the sewers of Tyneside, which were also approved and regulated by the TIC, and the number of which consistently grew across the TIC’s tenure until there were 270 active sewers draining into the Tyne when the TIC was replaced by the Port of Tyne Authority in 1968.

The Tyne was thus party to a vast array of industrial processes and substances that it had never encountered before after the TIC took control, and a dramatic increase in those which it had. The primary categories for these substances in terms of environmental concern break down to organic material, organic chemicals, inorganic chemicals, sediments, and hot water. The effects of heat on natural ecosystems can often be overlooked but the amount of water from the Tyne which was used for coolant and then ejected back into the river still warm was enough to deal considerable environmental damage, this hot water predominantly coming from iron works, steel mills, and refineries such as Crowley’s iron works at Swalwell. The warmer a body of water is, the less oxygen is dissolved into it, whilst at the same time warmer water increases the metabolic rate of organisms within it, thus increasing their demand for oxygen. A reduction in oxygen in the Tyne therefore meant a reduction in the amount of plant and animal life that could survive there.

The main culprit however in causing the deoxygenation of the Tyne was the discharge of organic material such as sewage and drainage from slaughterhouses, tanners, and flour mills, such as the Baltic Flour Mills at Gateshead. Once discharged these organic materials begin to decompose, the decomposition process being achieved by a flourishing of aerobic bacteria which are highly ‘oxygen hungry’ life forms. In the Tyne this occurred on such a large scale that the very first oxygenation test in 1912 concluded that there was ‘almost no oxygen’ in the river, which was alone nearly enough to end all life within. Once this had occurred it meant an increase of anaerobic bacteria, which produce foul smells. Other bacteria and viruses which were harmful to local river life, such as those of the Faecal Coliform or E. Coli varieties, also bred and spread quickly on this organic material.

Organic and inorganic chemicals were likely far larger killers of river life than bacteria and viruses however and were indeed the killers of bacteria and viruses as well. Salts, acids, mercury, arsenic, benzene, naphtha, cyanide, lead, and phenolic wastes were all being ejected into the river from mines, farms, sewers, oil refineries, and coking plants such as the Derwenthaugh Coke Works which alone in 1928 pumped 1kg of cyanide into the river for every ton of coke produced. These substances were toxic to almost all river life, and toxic even at low concentrations, which they were not in the Tyne, and together were the one factor that caused the most damage to the Tyne’s ecosystems and led to it being classed as biologically dead in 1957.

The dumping of sediments into the river, such as wood pulp, coal washings, and sludge was the one area where the TIC did attempt significant regulation. This was because of their dredging program, for which they did not want to create more work, and so they would inspect the discharges of factories to make sure nothing too solid was being ejected, first hiring Hugh and James Pattinson in 1895 to conduct tests to help them with this task. One substance they also attempted to prevent entering the river was oil from plants like the Benzol Works, which was the first place in the world to produce petrol from coal, because of the damage it caused to their property. It is evident therefore that the TIC would only step towards regulation if the environmental interests of the river aligned with their own economic concerns.

Turning Away from the Tyne

In 1910, a street of houses in Lemington called Bell’s Close was erected along the riverfront. What distinguished this street from others that came before it, however, was that it was facing backwards, away from the Tyne. Indeed, the backs of the houses didn’t even have windows, they had turned away from the water because it had become ugly, foul smelling, and dangerous. This was exemplative of the larger trend that had been taking place all along the river, of houses and town centres moving further and further away from the river, being demolished in favour of factories and warehouses. After the first and second world wars, when industrial production on the Tyne began to decline, this resulted in the complete abandonment of much of the riverside¸ what had historically been some of the most desirable land available. A committee set up in 1969, immediately after the dissolution of the TIC, wrote that where Newcastle’s quayside had previously been one of the most overcrowded regions in the country it had now become a ‘neglected back alley’. Humanity’s environmental impacts had impacted on themselves. In 100 years the TIC had overturned what had seemed an inalienable truth for thousands, that rivers were at the centre of human civilisation. By 1940, the 1969 committee wrote, ‘neither salmon nor children could enter its polluted waters’.

As the scale of the destruction became apparent, however, pressure mounted on the TIC from both the public and other organisations to do something about it. The primary driving force behind this was the TSC, which had been advocating stricter environmental regulation all throughout the TIC’s lifetime, but to little avail. In 1921 they helped set up the Standing Committee on River Pollution Tyne Sub-Committee (SCORP) which produced a number of reports with suggestions for how to improve the water quality, including a comprehensive sewerage treatment plan in 1936, but the TIC, the second world war, and a lack of funding blocked any progress. A Newcastle university report in 1957 said that public opinion ‘requires an improvement’ of the river environment and a 1958 motion in the house of commons recommended action for tackling pollution in the Tyne, but the TIC was as equally uncooperative with these as it would be with the Tyneside Joint Sewerage Board, set up in 1966. Just as with the Newcastle Corporation before it the culture of the TIC had become engrained, it saw itself as the heroic protector of orderly, profitable trade against the dangerous, unpredictable natural world. To a growing number of people however, the TIC had become the villain, too willing to sacrifice the picturesque for the profitable.

CONCLUSION

The success of the TIC was ultimately short lived when compared with its predecessor the Corporation of Newcastle, which lasted for nearly 400 years. For an environmental historian however this is not surprising, as they can appreciate the benefit that the Newcastle Corporation found in achieving a balanced relationship with the river on which it was reliant. Conversely, what the proceedings of TIC show us is that they did not look out for the health of the river, nor did they care for it. Instead they grew wealthy on the back of ‘robber industries’, trades that ‘carry the seeds of their own decline’. It cannot be denied that their works were marvels of engineering, and for some of the human population also brought great wealth, but to celebrate the reign of the TIC as the “heyday” of the river is a perverse anthropocentric notion that ignores the vast majority of Tyneside’s inhabitants. It operated in a way that was harmful to the health of all life based around the River Tyne, including the human population, and the scars it left are costing the region in the long run in the resources spent attempting to heal them. The modern Nile, Ganges, and Yangtze, whilst being far grander waterways, might do well to pause a moment and listen to the Tyne’s story, as they will find parallels and lessons within which they may wish to act upon.

Author/Publisher: Louis Lorenzo

Date of Publication: 24th of August 2019