Preface: A Subject of Scale

In its whole, the story of population in South America from 1492 to 1800CE is one of demographic collapse. At the low point of this period the continent would be witness to a population that reached but 1/5th the size of its pre-Columbian standard. However, taken individually, the huge variance in experience within South America during this period becomes apparent; from regions whose population figures fall and rise in dramatic peaks, to those that undulate composedly across modest crests.

Initially however, it is important to note the vast scale of this undertaking and the limitations therefore imposed, namely a limitation to the macro. Many of the studies concentrating on South-America in this field have been of a type that focus acutely on one specific area and are successful in realising the demography of such a space in fine detail. These studies range in size from David Noble Cook’s study into Peru over a period of 100 years to Brian M. Evans’ study of an Andean Village over a period of 43 years. The view herein over all South America over 308 years will draw on studies such as these but will not attempt to replicate them in outcome. The expansive scope of this article requires it to correlate broader trends and seek to contextualise them within a continent-wide context. This is a complimentary approach to the mathematical facet of this study which operates more effectively with larger pools of data. The ultimate achievement of this article is to plot the change of the indigenous and total population of South America over this period, as a collation of other studies done in this area alongside primary census data. Moreover, it will explain to what extent disease was the primary causation for demographic change and shall provide offerings as to the variance in population decline across five distinct regions within South America (see figure 1.). Furthermore, when the term ‘disease’ is used herein it is used as a collective term for multiple afflictions; this is due to the fact that there is much dispute as to which diseases affected which populations at what times, although it is generally accepted that smallpox, measles, and typhus were the main killers with the Variola Major strand of smallpox constituting the greatest killer overall.

The standard disclaimer must be applied here that the figures presented herein, although primarily drawn from census data of the period and believed by the author to be broadly correct, are bound inevitably to be inaccurate in many aspects. This is the challenge of applying a scientific approach to historical data. However, dealing with incomplete source material is the perpetual challenge of the historian and one that cannot be shied away from, lest no history be written at all.

Pre-Columbian South America

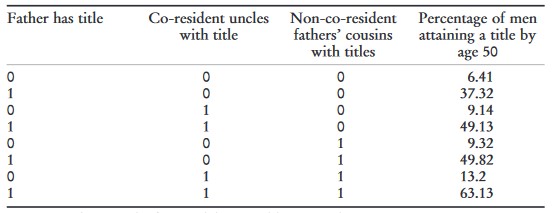

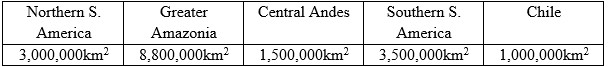

Before we begin to assess change across the continent we must first be clear in what we are assessing a change from. What was the makeup of South America in 1492? Estimates for the overall population for the region continue to exist in dispute however some mean figures have been produced for this article, in aggregation of several other estimates made over recent years. The central influence for these pre-Columbian figures continues to be the work of William M. Denevan and his text The Native Population of the Americas in 1492 which remains an excellent source on this topic. Ultimately the total population statistic reached for pre-Columbian South America in 1492 is 20,000,000. Across this study, this total figure is broken down into five regions across South America. These are: Northern S. America, Greater Amazonia, Central Andes, Southern S. America, and Chile. The continent has been split this way partially due to geographical differences in the five regions and partially to facilitate cross-comparison over time. If we were to use boundaries that shifted over time, such as the borders of nations, our comparisons would be less accurate. These borders are approximates of regions and are not intended, nor should not be taken, as accurate boundaries.

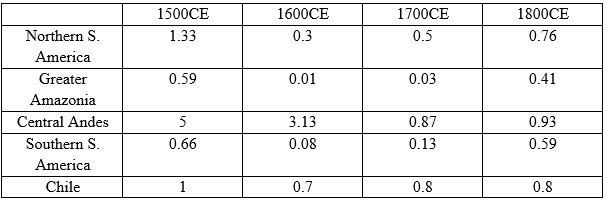

The regions identified in figure 1 are the geography to which the rest of this article is referenced to. Thus, the population split for South America in 1492 is as presented below.

These demographics aside, what other features can we ascribe to these five regions that might be important in a study of post-Columbian disease spread? For this study the focus lies on significant factors that can be compared across the five regions identified. These are: climate, geography, and patterns of settlement.

In terms of climate, for which the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system is used, our two most northerly regions of Northern S. America and Greater Amazonia can be described as ranging between a tropical (Aw) and equatorial climate (Af). These warm and wet conditions which comprise the great majority of these two regions are well suited to the spread of disease, particularly as they are prone to monsoon; we would therefore expect higher levels of mortality in these regions than in others. The Central Andes region contains a greater variance in climates due to its mountainous geography: it is mostly covered by a cold desert climate (BWk) but also contains large areas of semi-arid climate (BSk) and temperate oceanic climate (Cfb). We would expect these colder and drier conditions to be more effective at staying disease spread here. The Southern S. America region would mostly be classified as a warm oceanic climate (Cfa) with some areas of tropical (Aw) and semi-arid climates (BSh). This region can be described as susceptible to the spread of disease but not to the extent of Northern S. America and Greater Amazonia. Finally, in Chile we find areas of cold desert climate (BWk), temperate Mediterranean climate (Csb), and temperate oceanic climate (Cfb). This, in similar fashion to the Central Andes, is an area we would expect to find reduced mortality rates in due to these pathogen-hostile climatic factors.

The geography of the continent can be split into two areas on either side of the Andean mountain range which covers the regions of the Central Andes and Chile. These mountains are a dominant factor in the lower temperatures seen in these regions as discussed above. Additionally, the mountains help to curtail the spread of disease by limiting travel and isolating groups from one another. On the eastern side of this “Andean split” in Northern S. America we can identify the Guiana highlands as a geographical feature that would act similarly. This is also true for the Brazilian highlands in Greater Amazonia and Southern S. America. However, these highland areas will prove less effective at preventing disease spread in these regions as they do not cover them in entirety, unlike with the Andes, and thus their major comprisal of large lowland areas still allows disease to spread more efficiently.

For patterns of settlement across the continent: in clear majority we are discussing a dispersed population of peoples that do not gather into large permanent communities. This is the case for Northern S. America, Greater Amazonia, Southern S. America, and Chile. Certainly, there were areas of more concentrated populations within these regions, often along rivers and coastlines, but these were still clusters of villages rather than towns or cities. This type of isolated pattern of settlement is one which is often effective in curtailing the spread of disease, so we would expect regions with this pattern to be less susceptible to illness. In 1492 the exception to this rule was the area of the Central Andes, occupied in majority by the Inca Empire which was home to cities with populations of 700,000 or more such as Cusco, Quito, and Choquequiaro. In this case we would expect to see this area prove more susceptible to disease spread than others.

Three Hundred Years of Disease in South America

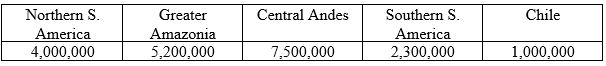

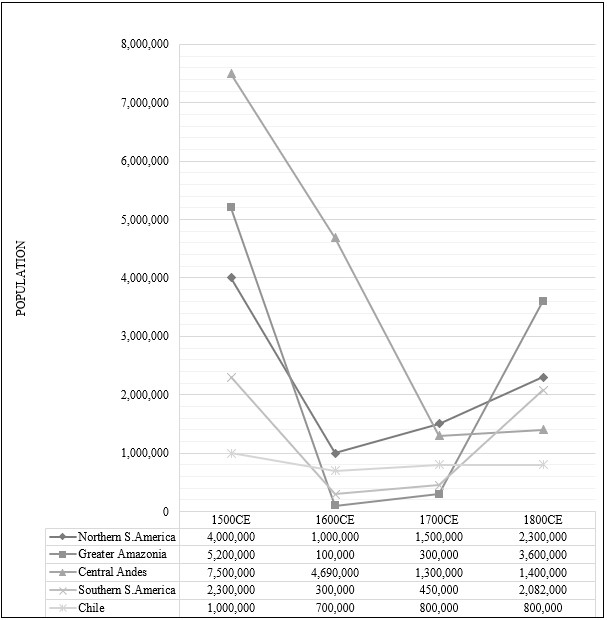

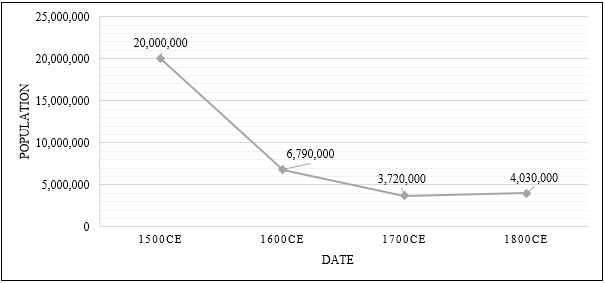

Population figures across this period, particularly during the first 100 years, are to be taken with a large margin of error. After 1600 the Spanish and Portuguese began taking censuses of the regions they controlled, spanning by this point almost all the continent, and so we do have primary statistics available to us that were not available for our pre-Columbian assessment. Even so, it is highly likely the numbers they give are low estimates, as even today our estimates ever increase for the number of indigenous on the continent. Nonetheless, by collating all these censuses in conjunction with our pre-Columbian estimate we can produce a graph that tracks the population of the continent over these 300 years.

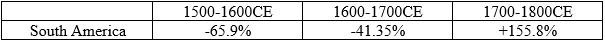

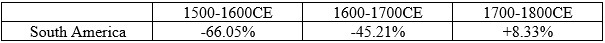

Using this data, we can also calculate the rate at which the population changes between these points, as seen in the table beneath.

These statistics show the immediate damage done to the continent and the recovery from that. However, it must be noted that these population statistics are not solely for indigenous peoples, they include all those people who have, either by choice or by force, moved to the continent during this time. This is what explains the 155.8% increase in population from 1700 to 1800, it is comprised of immigration, we would not expect a native population to recover at this rate. The question therefore asked becomes what is the rate of native population recovery, as supposed to simple population increase overall? For this we can utilise our regions; by splitting our demographics between these five zones, including those that saw large immigration and those that didn’t, we can determine the extent to which immigration as a factor has affected the overall population statistics.

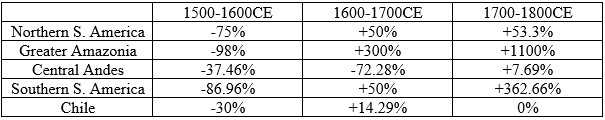

For this above graph we can also produce a population change rate table.

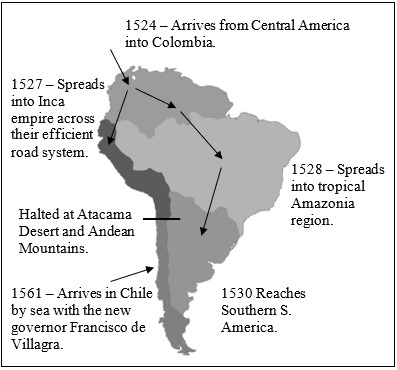

This information is enlightening in multiple aspects. From 1500 to 1600 we can immediately see that some areas have declined to far greater extent that others, namely Northern S. America, Greater Amazonia, and Southern S. America have declined at much higher rates that Chile and the Central Andes. This can be explained by the climates and geography of these regions which, as was explained above, are far more suited to preventing the spread of disease in the Central Andes and Chile than in the other regions. In Chile this can be further explained by noting that disease did not reach the region before 1561, much later than the other regions (see figure 9.). However, some Umbridge must be taken with the 98% decline figure for Greater Amazonia during this period. Of all the data drawn on for this study this figure seems the most inaccurate. Although it may well be true that mortality rates were high in this region due to its tropical climate, the 0.59 population density for this area would never allow such a drastic reduction (see figure 8.). This article would hazard that the rate of reduction would be closer to the 75% reduction seen in Northern S. America as these two regions have very similar climates and geographies. Nevertheless, in the absence of any further data the -98% figure will continue to be used.

From 1600-1700 the notable standout is the one region which continues to decline whilst the others begin to rise in population, the Central Andes. This is likely explained by the concentrated population density in this region which allowed for disease to continue to spread virulently, as seen in figure 8. By 1600 the other four regions all have populations densities beneath 1 compared to the Central Andes which sits at 3.13. At this point it may well be argued that these other four regions have reached a point beneath the ‘minimum concentration of hosts’ threshold whereas the Central Andes has not; this means their populations are now too small when compared to the size of their landmass to facilitate further disease spread. The well-developed road system of the Incas will have also allowed continual consistent movement of peoples around the empire; further facilitating dissemination of infection. This is especially crucial if you note the long incubation period of the two largest killers, smallpox and measles, which exist in the body for c.10 days before the person infected begins to show symptoms. The further a person is enabled to travel within these 10 days the faster these illnesses can spread. We can also see within the regions whose populations do rise the difference in the rates of the population increase. This is explained by immigration, not native recovery, and will be explored in depth with the assessment of the data between 1700 and 1800.

From 1700-1800 we can clearly identify the regions which are experiencing outside immigration and those which are not. Again, we see a divide made between the Andean regions of Chile and the Central Andes and the rest of the country. On the west side of the Andean split we see population figures that are struggling to begin a recovery towards pre-Colombian levels, with Chile’s population becoming stagnant and seeing no increase in the 100 years between 1700 and 1800. This is representative of how the native population across the country is recovering from the impact of disease: slowly. The reasons for this are numerous; one large factor is a decrease in fertility rates after disease has ravaged a population. This can be due to the disease itself physically affecting reproductive abilities or unbalancing the gender ratios in a population but can also be a result of social grief and stress. Recovery rates are also affected in the long term because disease results in higher mortality rates in the young population, who are the ones able to reproduce.

With our knowledge of the western side of the Andean split the extraordinary nature of the figures from the eastern side becomes apparent. Even the 53.3% increase seen in Northern S. America would be classed as an unprecedented event, with figures of over a 1000% increase existing in realms of fantasy. These statistics correlate well with the records kept by the Spanish and Portuguese of slaves imported during this period, which indicate c. 5,000,000 were imported into the Viceroyalties of Brazil, Rio de la Plata, and New Granada from 1700-1800. Using this data we can calculate how much of the increase in population on the east side of the Andean split is due to immigration. Taking Greater Amazonia as our example, given that it saw the greatest increase in immigration, we can take 10% as a generous figure for the increase in native population during this period. This would constitute only 30,000 of the 3,300,000-increase seen in population and means that 99.16% of the new population is imported. Using similar thought we can interpolate new data across all our existing figures produce a graph that tracks only the indigenous population statistics

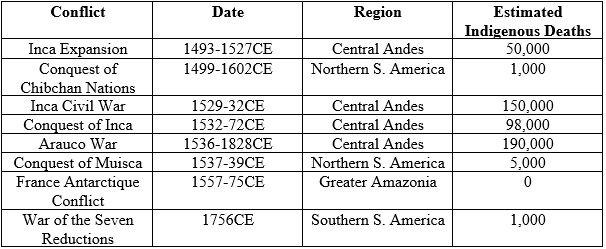

Now we have calculated the decrease in native population we must ask: to what extent is disease responsible for these deaths? It is understood that it is the major factor, but how far so? Let us examine the Spanish and Portuguese maltreatment of the indigenous to see the extent of their impact.

It is evident from this information that death from conflict may be considered a negligible factor when considering the overall indigenous population decline of South America. The single conflict with most meaningful impact on population is the Inca civil war which accounts for only 1.1% of the population decline from 1500 to 1600. The Arauco war is the cause of the most deaths but stretched over a far longer period, giving it less impact.

As for the encomienda and mita systems, alongside other forms of cruelties brought about by the Europeans, it is unknown how many died as a direct result of these persecutions as no records were kept, not even estimates. These, evidently, were not numbers the colonisers wanted recorded. Even if we did have such data it would be difficult to extricate deaths directly caused via cruelty and those that came tangentially because of it. We may still make some assessment of their material impact however; the one undisputable fact is that these systems helped facilitate the spread of disease through multiple means. They gathered previously dispersed populations into concentrated groups, forced them to travel long distances, and worked them into a state of weakness. All of which are ample conditions to facilitate infection. In this sense their impact on population decline may have been far greater than they are given credit for here. Nonetheless the ultimate cause of death is disease in majority by a far margin, as far as our statistics show us.

If we take our statistics from figures 10 and 11 and subtract population decline for reasons aside from disease we can produce an estimate of indigenous population decline specifically as a result of disease. We have calculated that approximately 1% of the population die as a result of warfare between our 100-year intervals, using a global average we can also calculate that approximately 1% can be accounted for by “natural causes” and accident. As discussed there are no statistics for the impact of systems such the encomienda but we must estimate they had some impact given the severity of their programmes, and have been given a 2% impact factor. Overall these account for 4% of the total indigenous population decline from 1500 to 1800. The total indigenous population decline from 1500 to 1700 (it’s lowest point) is 81.4%, so therefore the total decline as a result of disease before the population begins to rise is 77.4%. This means the total number of indigenous killed by disease from 1500 to 1700 is 15,480,000. It must also be noted for clarity that even after this point, as the population increases, indigenous peoples are still dying from disease and that some of these infections continue to plague areas of South America in the 21st century.

Ultimately this article has been able to track the population, indigenous and otherwise, of the South American continent from 1492 to 1800. It has provided reasoning for the variance in figures seen across the five identified regions and compared them against each other to infer further detail about the impacts of disease and other factors during this time. Although it is understood that these figures are approximates, it is nonetheless understood their significance in helping us understand this troubled period of history.

Author/Publisher: Louis Lorenzo

First Published: 19th of October 2018

Last Modified: 23rd October 2018 (Clarity)