Beyond the environment of the schoolhouse, the majority of the population encounter history through commercial products to a far greater extent than academic sources. Whether through theatre, film, television, toys, games, advertisements, or other means, history competes in a marketplace of ideas for people’s money and, perhaps more importantly, their attention. Whilst historians would likely prefer greater public engagement with their academic work, they have not recoiled from this state of affairs and have instead sought to engage with the public field in order to understand and influence the teaching of history outside of controlled environments such as classrooms and museums. Indeed, public history and public historians are often at the centre of projects seeking to enhance and rejuvenate public environments. With the rise of public history, academic interest has increasingly turned its attention on the multitude of mediums through which history is communicated. Literature on film is prevalent and the study of digital games in particular has been expanding rapidly as the form has been paid increasing attention by academics. With computer games, particular interest has been taken in what it means for a person to actively participate in personal historical simulations and embody a person or idea of a period, and how this intersects with ‘particular representations, generalizations, or interpretations’ a game forwards. It has been noted that people having a “personal experience” of history through the ‘projective stance’ of play tends to engender empathy and a sense of personal understanding of history that can keep a person engaged in a topic they would otherwise overlook, but can also mean misleading historical narratives become more deeply engrained in a person’s conceptualisations of a period than with other media.

However, somewhat neglected in the study of play and historical learning has been analysis of how games in a non-digital space can act as communicators of history. This is despite the fact that tabletop games have seen an exponential sales growth of between 20% and 40% every year since 2000 worldwide. As the medium expands, and over 5000 new titles are published every year, it is sensible to examine what these experiences say to their audiences, and how they utilise history for marketing, storytelling, gameplay, and learning. Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, a foundational text in the study of play as an element of culture wrote that learning ‘does not come from play like a baby detaching itself from the womb: it arises in and as play, and never leaves it’, so what is learned in tabletop play? This essay will firstly contextualise the position of historical tabletop games within the current cultural landscape and examine how they communicate history through their mechanics, who for, and why. It will also ask: what historical understanding do people take away from these experiences? How is the medium distinct from others such as literature, film, and digital games? How does the unique physicality of tabletop games as a medium shape their ability as communicators? Furthermore, what is their capacity to explore complex, nuanced discussions?

Of course, what this essay cannot do is fully convey how these games operate in play, if you have ever tried to teach a game to someone before, you know that at a certain point you have to stop explaining the rules and let them learn through play itself. This is a notable point, that there are forms of knowledge that cannot simply be told, they must be experienced, interacted with. As Jean Piaget explained in his landmark text The Origins of Intelligence in Children: ‘Knowledge is not a copy of reality… to know is to modify, to transform’. As in chemistry or mathematics, theoretical understandings, or hypotheses, must be tested and experimented with in order to prove their merit. In history this is generally achieved through debate amongst academics but play itself offers a method of historical experimentation.

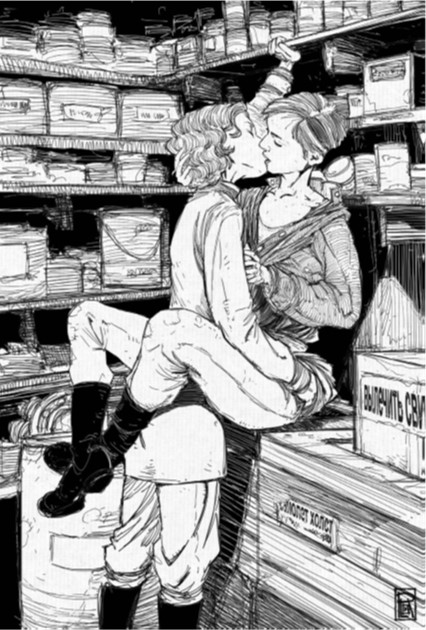

One of the most popular themes for board games in western markets, as with a great deal of media generally, is the world wars of the 20th century. In order to tackle the questions this essay posits it will direct its focus towards two titles that engage with this period of history and draw out the narratives they teach to their audience, as well ourselves as critical readers, about how systems of gameplay intersect with systems of warfare. The two titles chosen, Diplomacy and Nachthexen, were done so after a period of playtesting and experimentation as examples that demonstrate some of the most promising aspects of tabletop games as catalysts for learning. Their place in the broader canon and how they deviate, or conform with, the norm will also be discussed. In the board game Diplomacy, players act as the leaders of European nations during the first world war, negotiating and strategizing with one another in a battle of wits to determine which one, or multiple, among them will emerge as victors. The second, and rather different, case-study is the role-playing game Nachthexen. Players of Nachthexen, otherwise known as Night Witches step into the shoes of the pilots who flew with the all-female 588th Soviet Night Bomber regiment and “play out” their day-to-day lives through mechanic-prompted improvisation. Both games offer interesting and different methods of understanding history that would be difficult to replicate through alternative means; they are by no means academic, but are good case studies of how tabletop games are being used to communicate serious historical lessons about 20th century warfare to a general audience.

As alluded to, the existing historical literature that examines tabletop games as communicators of history is light, with some notable exceptions. Primarily the literature has revolved around how academics can create individual custom games, or modify existing ones, for use in a classroom or seminar environment. In Benjamin Hoy’s study of this topic, he concluded that the way board games adapt historical events into mechanics that must be comprehensible for their players meant they induced in students ‘a more reflective stance on the importance of structural factors in influencing perceptions of right and wrong’. Generally, tabletop games focus less on telling a narrative, and more on creating a set of systems that will create an emergent narrative during play. In other words, they have less of an authorial “voice” than other media, and as such lean more towards emphasising systemic aspects of historical change. Hoy was optimistic that tabletop games could be used to teach ‘not only historical content, but also research methodologies and historical empathy’. As custom learning tools, the majority of other studies in this area reached comparable conclusions, Damien Huffer and Marc Oxenham additionally noting that tabletop games are far less ‘time/resource intensive’ than electronic alternatives for classroom environments, and more universally accessible. Mark Hayse has also argued that they serve a double-purpose as also being providers of what he calls ‘21st century skills’ in addition to historical knowledge, these namely being collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and adaptability. Maria Northcote concluded her assessment by stating that her students’:

‘contextual understanding has broadened, their level of knowledge and engagement has grown, and the deep learning they have experienced has ensured that they will retain the learned outcomes for a long time.’

On the other hand, no study to date has advocated for tabletop play as being better than any existing methods of teaching, rather they suggest that it could be used in conjunction with more traditional techniques to highlight specific aspects of a subject matter and keep students engaged. A survey from Oklahoma State University expressed doubts as to their ability to properly convey ‘a series of complex issues’ but was ultimately positive on the idea of tabletop games as learning tools. However, what appears missing from the contemporary literature is examination of tabletop experiences such as Nachthexen, which by merit of being a role playing game (RPG) does place emphasis on narrative over systems. More importantly, there has been no assessment of games designed for use at home, not as part of an academic curriculum. The existing historiography generally concludes that tabletop games in a controlled environment can act as useful communicators of history, but how does this change when moved from the classroom to the living room?

One of the first differences between a classroom game and a living room game is that the latter is a commercial product that must be sold to its audience, not simply presented. As such historical topics that audiences have some familiarity with are often chosen as “hooks” for games, thus the prevalence of world war themed titles. Therefore, when examining Diplomacy and Nachthexen it is important to understand the markets into which they are sold, and the audience’s motivations for purchasing them. The general western tabletop market today is not inclined towards a particular gender, however the subsection of “strategy games” is more prevalent in male markets whereas that of “role playing game” is more prevalent in female markets. This means that the audience for Diplomacy tends towards men, this being especially true when the original incarnation of the game was released in 1954. Nachthexen however, as a more modern design with more focus on interaction and inter-personal relationships, does not tend significantly toward any gender. The average age of the target demographic for these games is 35, and the overwhelming majority of sales have been made in white, western nations. This means that these games are being played by an audience that will likely have little direct personal connection to the historical events being explored. They will however, due to their being educated in western schooling and culture, have a greater understanding of the subject matter than many other historical periods. Indeed, this is part of the reason why so many games use this period as a theme, because it can be easily marketed. Players choose to buy these sorts of games not only to enjoy playing with their mechanics, but to engage with the history on which these games are based. That is an integral part of the desired experience and what is being sold. By choosing to play historically-based games, players have demonstrated a desire to expand, challenge, or draw upon their own historical knowledge whilst playing and will frame their own actions in the game as, to a certain extent, engaging with the past.

Larry Harris, designer of Axis and Allies,described Diplomacy as a ‘masterpiece [that] should be part of every high school curriculum… it teaches history, geography, the art of political negotiation, and something else — some healthy critical scepticism’. Allan Calhamer, a Harvard law school graduate and designer of Diplomacy, also believed his game said something about history, and garnered enough respect to be able to publish his own book in 1999 titled “Calhamer on Diplomacy: The Boardgame Diplomacy and Diplomatic History”. The game’s design, dating to the 1950s, is a particularly interesting subject to examine due to its enduring popularity, having persisted where so many alternatives have fallen into relative obscurity. The game’s popularity has meant that aside from its physical incarnation, it is also played in “play-by-post” and “play-by-email” formats as well as through a dedicated website. It even has its own quarterly journal, “Diplomacy World”, which has been running since 1974 and includes discussion on the game and the community around it. Some of its most famous proponents included John F. Kennedy, Walter Cronkite, and Henry Kissinger. The question therefore is, what is it that has made Diplomacy’s unique design stand the test of time and how does this relate to its ability to communicate history, given that the game contains no written historical accounts, or accurate representations of warfare?

At first appearance the game resembles many other titles such as Axis and Allies, World in Flames, or Risk; a top-down map with various pawns placed about it. However, whereas these games focus on simulating military tactics, supply chains, and various other systems of warfare, Diplomacy is far more abstracted. The focus is not placed on combat but, as the name suggests, on diplomacy. Indeed, the mechanics of the game as written are relatively simple, every player may move each of their pieces one space each turn, and if two pieces run into one another they will fight. However, because each piece’s strength is exactly equivalent, combat will always end in a draw unless they assign an adjacent piece to assist in the fight rather than move itself. The key innovation of Diplomacy’s design was that all pieces would move simultaneously at the very end of each round, after every player had already secretly decided what theirs would be doing. The actual movement and combat therefore, constitutes a fraction of the game compared to the discussion period beforehand wherein players form pacts and alliances, make promises, and have secretive discussions. There is no luck of the draw, so this is your only path to victory. Perhaps you agree to demilitarise a border, or assist with defending an ally’s city, pre-emptively decide how you will carve up a neighbouring land between you once you have won the war. The kicker to all of this being that nobody is obligated to tell the truth or keep a promise, and the game becomes one of tense, analytical, sceptical play. There are no imperatives to fight a particular person, or ally with one, but what drives player decision more than anything is paranoia that somebody else will act first, or the suspicion that your supposed ally is planning to stab you in the back. It is an experience of ‘maneuver rather than annihilation’.

Instead of teaching minutiae, Diplomacy leans into the abstracting nature of board game design to place its players in the position of country-leaders jostling for power and influence. The country that players start as has a significant impact on their style of negotiation, with central European powers constantly fearing being flanked, the British player preciously guarding the seas that surround them, and the Russian player struggling to police their vast borders. From the offset the game emphasises geographical factors in shaping the mindset of a nation and their military strategies. By focussing on the social aspect of tabletop play, an element absent in other mediums, after a game of Diplomacy players have not learnt specific dates or models of battleship, but they have developed a deep understanding around the complications of diplomatic negotiation. Even though players are sitting around a table with their friends, small movements that may have been perfectly innocent are interpreted as acts of aggression; nations suddenly ally against a player that is seen to be a threat but will just as easily turn against one another in opportunistic land-grabs if they perceive weakness. Players gain insights, and a form of “first-hand” experience, in how a war such as the first world war could be allowed to happen by intersecting chains of decision making often set in motion by a relatively minor act. Furthermore, a real strength of a Diplomacy in this context is its indeterminism. By engaging with a dynamic, shifting, unpredictable simulation, players recontextualise the history in their minds as not being a predetermined bullet-point list of events, as it is often thought about, but something which was a contextual, fluctuating reality.

However, whilst extremely helpful in these respects, Diplomacy only functions as a helpful learning tool in an environment where the player has a base understanding of the history it tackles. First and foremost, and as is the case with many of its contemporaries, the most glaring omissions in Diplomacy’s historical narrative are the roles of the foot-soldiers and civilians in warfare. To teach the lessons it does about warfare in an engaging manner, which mostly relate to leaders and figureheads, the game chooses to simplify a great deal about the “common” experience of war. The people who work in the factories and fight on the battlegrounds are reduced to pawns on a map whose welfare players care for only as much as they are able to continue fighting on their behalf. It is a game that emphasises the role of the strategist and the general over all others, partly because a game that included such details on this broad scale would become extremely complex to play. However, it could also be conversely argued that for those with some understanding of this period, this is another insight that Diplomacy provides on how easy it can be to dehumanise people when thinking in strategic, large-scale terms. In these senses, Diplomacy is a game that produces empathetic (not necessarily sympathetic) responses in its players towards the great war’s strategists and generals, a group whose mindsets “ordinary” people have often found difficult to comprehend. It is this access empathy, perhaps, that gives the game its fearsome friendship-testing reputation, as one review attests: ‘I have seen people go literally white with shock when moves were read out; I have seen punches thrown’.

Nachthexen offers a completely different experience to that of Diplomacy, and one that does focus on the ordinary person over those in positions of power. It is one part of a new wave of modern tabletop games, alongside titles like This War of Mine and Carry: A Game About War, that seek to tackle complicated issues in a far more adult manner than games have done so in the past, as the audience for tabletop games grows older over time. It is a far less abstracted experience than Diplomacy, with a focus on smaller personal details. Nachthexen can achieve this style of storytelling because of the style of game, mechanically, that it is. In a role-playing game (RPG), the aim of the experience for the players is to step into the shoes of a person and pretend that they are them whilst in the game. Every player will play a different character and will interact with one another and respond to events happening in the game as if they were that person. The concept is similar to that of improvised theatre, where the rules and objectives of the exercise are far less defined than in a game like Diplomacy and the only real goal for the players is to tell an interesting story together. It is an exercise in empathy. As Juliano Pereira da Silva wrote in The Machinery of Time Moved to Imagination, this form of play is ‘a venture where people show the ability to reconstruct the goals, feelings, values and beliefs of others, accepting that they may be different from their own’. But to what extent does it act as a tool for understanding history? And how does it use history as a background canvas on which to paint the fictions invented by the players?

By its own description Nachthexen is a game ‘thoroughly rooted in real history’ and it makes a number of efforts to provide the players with genuine historical information about the broader history of the period with which they can contextualise their actions within the game. Specifically it focusses on the role of women in soviet aviation during the second world war and the additional obstacles they faced alongside all the regular troubles of warfare, including sexism and discriminatory attitudes towards lesbianism. Although the players are acting out fictional characters, the world those characters inhabit is intended to be an authentic representation of the real history so that players may “personally” experience a life as one of these women. Through this roleplay a player will learn some specifics around types of aircraft, military command structures, institutionalised sexism, and other such realties. However, more essential to the experience is that the players learn to empathise with individuals, and appreciate the multitudinous small tragedies that war produces which can often be lost into a sea of incomprehensible casualty statistics. As Karen Schrier puts it, engaging with a game such as Nachthexen ‘enables the skills and thought processes needed to make complex and quotidian ethical decisions, experiment with mistakes and consequences, and reflect on them’. This is a type of applied knowledge, and such reflection is a fairly complex historical thought process that is not generally taught in either school or university classroom environments, being reserved for historians themselves. As with Diplomacy, this form of historical communication is a specialisation of tabletop games, and one that utilises the social aspects of the medium. This can be a powerful learning tool as when thinking of the history, the player has a psychological framework with which they can place themselves into that past and therefore empathise or at least understand life experiences drastically different to their own. They make choices about how to respond to, influence, and control the “moving parts” of the historical processes in their environment. Through this methodology, social learning becomes active learning. As Barbara Varenhorst phrases it, this form of play allows people ‘to perform intellectual tasks requiring the use of abstract rules or theories well before they can say what those rules or theories are’.

However, even more so than Diplomacy, this form of understanding history can be dangerous as well as enlightening. The game does state to its audience that although it is grounded in reality it takes ‘liberties with the facts’, but the overall impression it gives is that it is telling a realistic story, and indeed that is a central element of its marketing because audiences desire authenticity. Ultimately the game is about storytelling over historical re-enactment and would rather players deviated from reality to tell a good tale over the opposite. Problems here may then arise when the line between fact and fiction becomes blurred and players may come away with incorrect impressions about certain historical intricacies. Generally, players’ understandings on a broader scale will be accurate, because they only improvise characters within the “world” in which they play, rather than the world itself. However, on more personal levels, it is significantly harder for players to be able to tell which elements of their experience could be said to reflect historical fact: which are authentic, and which are fiction. As one reviewer wrote: ‘the fact that it is also historical, documented, real makes it resonate all the more’. This is compounded furthermore when considering that players have the ability to deliberately twist the facts to make them better serve the narrative or because they don’t want to tackle certain issues. Even more problematic than this could be players taking personal ownership over a history that is not theirs, because they have stories, or ‘expedition reports’, that could serve to rival and undermine the very real struggles of the women of the 588th regiment. However, this is a problem that exists only in theory as supposed to in practice and one that is not an intention of the designers who make a clear distinction between the real history, and the reality-adjacent history of their game.

Tabletop games are not perfectly adapted to communicating history in a forthright manner, just as with any form outside of a lengthy monograph or lecture, but they do have the potential to capitalise on the strengths of their medium in interesting and unusual ways in order to teach historical lessons. If we think of the ‘mind as an instrument to be developed rather than a receptacle to be filled’, what Diplomacy and Nachthexen offer is a manner of communicating history to a general audience that focusses on more abstract, systemic principles over technicalities. The physical constraints of the tabletop game, an object that must be relatively small, easy, and quick to play, create this limitation to work within. However, the advantages of utilising social play to get players to engage in collaborative exercises of empathy is a relatively unexplored tool that has the capability to teach powerful lessons about the past. As Delmore Schwartz said it, ‘In dreams begin responsibilities’.

Author/Publisher: Louis Lorenzo

Date of Publication: 2nd of December 2020